What's the story behind Parylenes?

What makes organic polymers so special

- In 1947, a chemist named Michael Szwarc came across something unique.

- He discovered that the substance xylene leaves a transparent precipitate on cool surfaces when exposed to very high temperatures. This film, which remains at temperatures up to 1000 degrees, received the name poly(p-xylylene).

- As early as 1965, the discovery was refined (in the Groham method by Union Carbide) in such a way that the step towards commercial use (for example, for space-flight projects) became possible. Because of this somewhat cumbersome, complicated name, the very effective polymer was ultimately renamed “parylene“.

The useful properties of paryleneat a glance

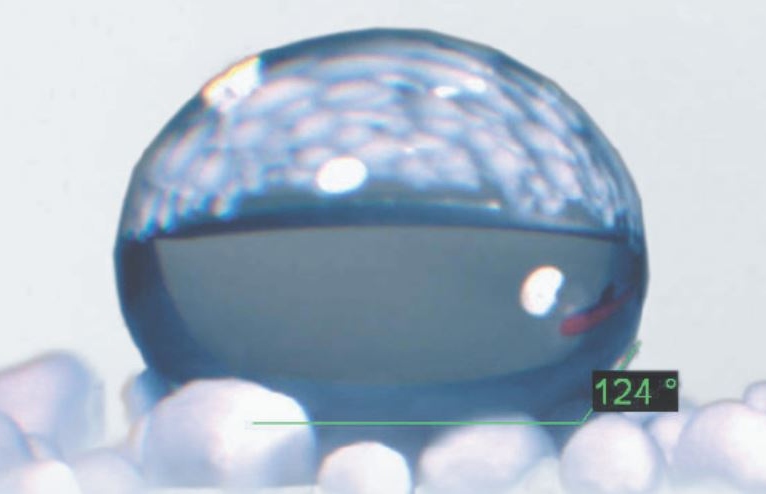

Parylene is an inert, water-repellent, biocompatible, optically transparent, chemically resistant, polymeric coating material that has a wide range of industrial applications.

Features at a glance

- Good sliding properties

- Hydrophobic surface

- Chemically resistant with barrier effect to organic and inorganic media (acids, alkalis, gases, water vapour).

- Electrically insulating, high dielectric strength

- Biocompatible and biostable coating

- Thin, transparent and pinhole-free coating from 2µm

- Very high gap capability for complex substrates

- Excellent corrosion protection

- Homogeneous shift training

- No outgassing

Abrasion-resistant

The parylene coating is applied to the substrate material under vacuum by condensation from the gas phase as a non-porous and transparent polymer film. Virtually any vacuum-suitable substrate material such as metal, glass, paper, lacquer, plastic, ferrite and silicon, as well as objects such as plants, insects or archaeological artefacts can be coated with parylene.

Due to the gaseous deposition, the parylene even reaches and coats areas and structures that are not coated with liquid-based processes, such as sharp edges or tops or thin and deep gaps. The separation from the gas phase allows an almost total encapsulation of the substrate surface compared to covering the surface with alternative coating methods. Layer thicknesses of 0.1 to 100 µm can be achieved in one pass.

Many of the other liquid types of coating have gas inclusions and also tend to contract locally even at a moderate tension of the surface. This results in weak points, such as gaps, variable layer thicknesses and edge alignment. These are characteristics that reduce product quality in general.

Weak points such as these cannot appear in parylenes. Due to the polymerisation from the gas phase, the individual molecules can line up closely together.